They’re long.

It’s ridiculous how long they are, right?

I was in high school workshopping five-page short stories and sixteen-line poems when I decided the time had come to write a Grown-Up Novel. Not one of the copy-cat novels I’d written as a kid (mostly less arresting iterations of Redwall or The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle) but my first official, real-life, sell to a publisher someday novel.

Unfortunately, my first attempt ended up being five pages.

My second attempt? Twenty pages.

I didn’t have an issue with commitment or focus. No, the problem was that every time I’d start a story, the arc in my head — the pace of it, the scale of the character’s decision making, the beginning to end change in the story — always resolved itself in two to five scenes. I could look at the page counts in the genres I was trying to emulate. I could read all of the word count guidelines, but before I knew it, my story was just … over.

I need to think bigger, I thought! Bigger ideas! Bigger plots! Life and death and corporate espionage! That novel, an adult dystopian sci-fi murder mystery about corporate greed, was 200 pages of meandering nonsense. Clearly more words wasn’t the only thing my novel-writing needed.

the storyteller’s secret code

The answer came to me in graduate school–or rather, was taught to me in graduate school by my storytelling professor, Dr. Brian Sturm. A professional storyteller himself, Dr. Sturm advised all of us in his storytelling classes to think of our story not as a text to memorize but as a series of 5-6 scenes to tell our audience about. For example:

- Three little pigs set off into the world to seek their fortunes.

- The first little pig built a house out of straw, but the wolf blew it down.

- The second little pig built a house out of sticks, but the wolf blew it down.

- The third little pig built a house out of bricks, and the wolf couldn’t blow it down.

- The third little pig lived happily ever after.

Veteran story listeners can glance at these scenes and begin filling in details. The first pig was the laziest. The first vendor he passed on the road was selling straw, so he stopped. His feet were so tired! And the wolf didn’t just blow down the house. No, he huffed and he puffed and he blew the house down. If you can rattle off the five story points above, you can draw on your general cultural knowledge of European folktales and your familiarity with this story in particular to flesh out the details as you speak in front of audience. With minimal memorization required, you can have a large rolodex of stories at your disposal when you visit libraries or festivals. Just call up the outline in your mind, and off you go.

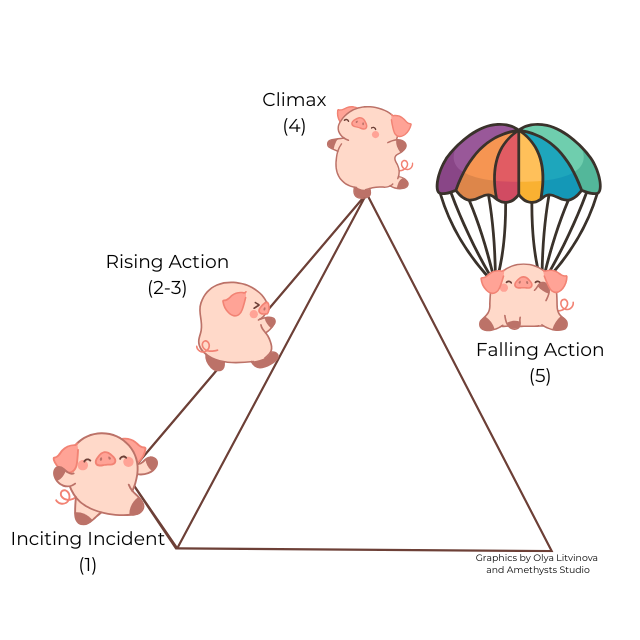

If you read books about writing, you may notice something else about my outline of the three little pigs. It fits pretty perfectly into Freytag’s Pyramid:

This particular structure is common in European-heritage stories, including films and novels. Three Act Structure also divides neatly into five scenes (inciting incident, first major plot point, midpoint, second major plot point, climax). But five isn’t a magic number, and the right number of major plot points depends on the story you’re telling and its–and your—cultural context. For her stunning novel Firekeeper’s Daughter, Chippewa author Angeline Boulley based her structure on the four-way division of the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community’s medicine wheel.

stretching the accordion

All of this is well and good, you’re thinking, but “The Three Little Pigs” isn’t a novel. And Firekeeper’s Daughter has way (way, way, WAY) more than four plot points. So how do you stretch a dinky little 4-5 point outline into a 400 page novel?

While thriller writers like Angeline Boulley may have a list of juicy secrets for their protagonists to uncover in order to take on the bad guys, the harder task is finding an arc that isn’t a litany of disconnected actions. What makes Firekeeper’s Daughter such an arresting novel is the rich development of the characters, especially the protagonist, Daunis, who struggles to develop her sense of identity and self-worth within a community she doesn’t always feel connected to–a struggle that unfolds along with the external thriller plot, both influencing and being influenced by those dramatic events.

I don’t know Angeline’s process, but when I write, figuring out which events go where and how they relate to the richness of character and theme is where the accordion comes in. No one grows and changes in a bare-bones tale of “The Three Little Pigs,” but character development is the heart and soul of a YA novel and must be intrinsically tied to any external action of the plot.

My favorite book about writing is John Truby’s The Anatomy of Story. Among his many excellent insights, he defines a story revelation as “a surprising piece of new information. This information forces [the protagonist] to make a decision and move in a new direction. It also causes him to adjust his desire and his motive. . . . The more revelations you have, the richer and more complex the plot.”

Don’t let the dramatic connotations of the word “revelation” fool you. This applies to quiet plots as much as loud plots. The pattern of Revelation -> Decision -> Changed Desire and/or Motive is thoroughly rooted in character and lends itself as much to a story about two friends growing apart as it does to … well, dystopian sci-fi murder mysteries about corporate greed. There’s plenty of room in a story for twisty plot-centric surprises, too, but Truby’s character-centered philosophy has helped me to avoid the trap of throwing a bunch of action on a page to make a story novel-length.

When I’m planning, I make sure that each of my bare-bones outline points is tied to either a choice my main character makes or a revelation that changes the way she understands the story she’s living out. I ask myself…

The answers to these questions start filling in details of the story in such a way that everything is oriented toward my larger beginning-to-end story arc. If the answer to one of these questions feels like a big scene (e.g., in order for Jess to realize she’s being a jerk, she needs to have a fight with Cam), then I accordion it out even more (what are 3-5 little moments that could pick at Cam’s nerves with increasing intensity throughout the first half of the book so that his outburst at the midpoint doesn’t come out of nowhere?) Even if they don’t survive revision, in a first draft, none of these details are extraneous because they all help me understand my character motivations and flesh out my themes.

leaving room for discovery

Sometimes I don’t know exactly what will happen. I’ll leave a note in my outline like [SOMETHING HAPPENS TO MAKE HER REALIZE IMPORTANT THING, IDK]. In the example above, from my novel Reasons to Hate Me, I would just throw into my outline <Jess does something annoying and Cam is annoyed,> letting my protagonist’s annoying antics unfold organically as I told the story. Remembering my storytelling training, it’s not about the exact words you say (or the case of writing a novel, the exact scenes that you write) as long as you’re traveling down the correct, arcing road that will take you from point 1 all the way to point 5.

Of course, as the maxim says, writing is rewriting. I frequently wind up with a lopsided story, or a character arc that feels too flat or to jumpy, or overwrought themes (or under-wrought themes) or a subplot that just doesn’t pan out. But once I have a whole book-length book on paper, it’s much easier to see the specific problems and shape it into the story I want to tell than it is when I’m staring at the blinking cursor on an empty page in my word processor.

Because novels are long–dauntingly, stupidly long. But if you open the accordion slowly, a first draft can be full of pleasant surprises, for the characters and their author.